I suppose that the prerogative I'm imagining for my generation in their particular task of problem-solving can be divided into two components. One component is the actual endeavor of healing and rebuilding social and ecological systems. The other, which is more of a personal mission that I don't really expect everyone to take up, is the re-appropriation of mythic thought into our vernacular language. I want to make the distinction of spoken language because I think that mythic thought is well-handled by visionary art, science fiction and (most) music. But it is in our common parlance that I have found a lack.

As readily as humans form groups, humans make myths - we are storytellers to the core. Buckminster Fuller would probably point out that we are physiologically predisposed to storytelling, and many other abstract activities besides, since if you compare the way we are shaped to any other animal, we're pretty much brains on a stick. Form follows function. Anteaters have straws as noses, giraffes have long necks, and humans have huge brains and opposable thumbs. And I have no idea why platypi look like that. So then if we can read a function from our form, We are designers and builders - and we will design invisible structures as well as visible ones. These invisible structures are our world-views, our world-maps, our myths. Our language is full of fiction and metaphor, even at the sentence level... as agency is what holds grammar together. (Agency holds...) With simple sentences we tell little stories all the time. It is a myth for me to say that the sun will rise tomorrow morning, as we all know it is really the earth that moves, but according to my perceptual experience, the sun appears to rise. Tailoring speech to our perceptual experience rather than tailoring it to "scientific truth" has obvious advantages - it allows us to succinctly transmit strategically valuable information. In studying the larger mythic structures we've built and the people whom they have served, it's clear that truth and facticity do not coincide at that scale either - nor do they have to. Something can be true without being factual. Culturally significant myths arose from unique dialectics between a people and their ecological niche... and there are tons and tons of those on this earth. That's a lotta truths.

The value of mythic thought has fallen through the cracks in the course of the development of our economic infrastructure, and has often been displaced by an obsession with reductionist science, which really only serves industry, and not the advancement of holistic knowlegde. We've been experiencing increasing loss of participation with our natural environment on individual and collective levels, and the experiences of these two spheres - the individual and the collective - feed and reinforce each other. Collective disconnection with animate forces of nature has consequently shaped our ways of speaking - literally our figures of speech - and this naturally creates a winnowing of our perception. Since language is something we can all consensually agree upon - and perception is not - language often succeeds in modulating perceptual experience to a certain degree. The linguist Edward Sapir said "We see and hear and otherwise experience very largely as we do because the language habits of our community predispose certain choices of interpretation." And indeed, the non-human animate aspects of nature are not as present in our language because they are not as present to our senses. And when they are not well-represented in our language, we lose to opportunity to believe in them - we are not re-minded. We are, however, well equipped to be reminded - we have all the gear necessary - all it takes is some fearless immersion in the woods, or an evening stargazing when there's no moon...

David Abram writes "The perceptual reciprocity between our sensing bodies and the animate, expressive landscape both engenders and supports our more conscious, linguistic reciprocity with others. The complex interchange we call "language" is rooted in the non-verbal exchange always already going on between our own flesh and the flesh of the world. Human languages, then, are informed not only by the structures of the human body and the human community, but by the evocative shapes and patterns of the more-than-human terrain."

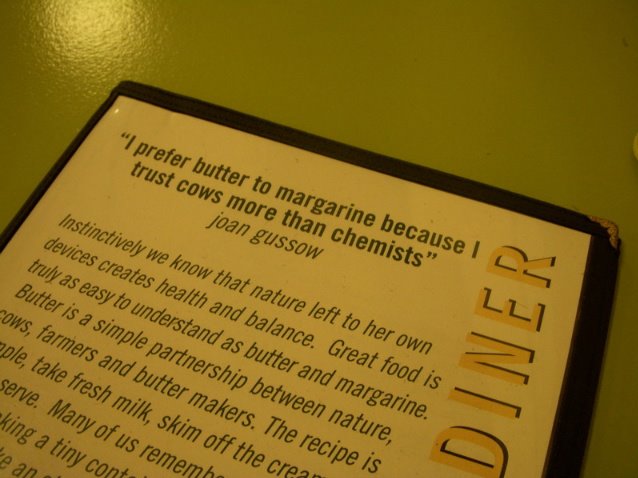

Loss of participation with our natural environment - whether it's gardening, hunting, animal husbandry, building with natural materials, or just sleeping outside - is correlated to loss of mythic language. How then do we communicate with each other in the vernacular about our perceptual orientation in the world? I know I would be hard pressed to explain the magical experience of drumming around a fire with scientific language.

Academic papers about quantum mechanics written in English are still incomprehensible to me, because I haven't learned the language that you learn when you study physics at that high of a level. In that same way, the great myths and oracles passed on by bards and shamans are similarly notated - they are condensations of information that go beyond the semantic "carrying capacity" of our everyday speech. A creation myth and paper written by someone with two PhDs both represent instances of using words as meta-symbols - symbols of symbols. But essentially what it means is that their meaning is not apparent to just anyone, but perhaps only apparent to a few people, and then all the rest have to work for it.

Animistic world-views and myths, where forces of nature are embodied and given agency, are ways of mapping the world. Myth-making and world-building are ways of translating the chaotic 'foreign language' of the environment into symbolic schema that can inform human action and orientation in social, natural and indeed super-natural environments. Mapping is a tactical endeavor, enabling a certain kind of navigation through the world, whether through landscape or 'mindscape'. This "mapmaking", whether through invisible or visible mediums, is arguably a universal among humans possessing language. Science is also a way of mapping - the mapmakers simply follow a different set of rules. A professor of mine put it this way: the epistemological function of science is "to make the unknown known" through a process that is characterized by falsification, and religion's function is "to preserve an autonomy for the unknown." I believe that we don't have to choose between the two... and why not plant these two trees next to each other, and see what grows in their collective shade?

Why farmpunk?

A farmpunk could be described as a neo-agrarian who approaches [agri]culture, community development and/or design with an anarchistic hacker ethos. "Cyber-agrarian" could supplant neo-agrarian, indicating a back-to-the-land perspective that stands apart from past movements because it is heavily informed by conceptual integration in a post-industrial information society (thus "forward to the land" perhaps?) The art and science of modern ecological design—and ultimately, adapting to post-collapse contexts—will be best achieved through the combined arts of cybermancy and geomancy; an embrace of myth and ritual as eco-technologies. In other words: the old ways of bushcraft and woodlore can be combined with modern technoscience (merely another form of lore) in open and decentralized ways that go beyond pure anarcho-primitivism. This blog is an example of just that. Throughout, natural ecologies must be seen as the original cybernetic systems.

**What we call for at the farmpunk headquarters**

°Freedom of information

°Ground-up action + top-down perspectives

°Local agricultural systems (adhering to permaculture/biodynamic principles) as the nuclei of economies

°Bioregional autonomy

°Computers are optional but can be used for good—see peer to peer tech, social media for direct popular management of natural or political disasters (e.g. Arab Spring), or the mission of the hacker collective Anonymous

°Computers are optional but can be used for good—see peer to peer tech, social media for direct popular management of natural or political disasters (e.g. Arab Spring), or the mission of the hacker collective Anonymous

°You

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment